Originally published in The Library of Congress by Stephanie Hall, 5 June 2020

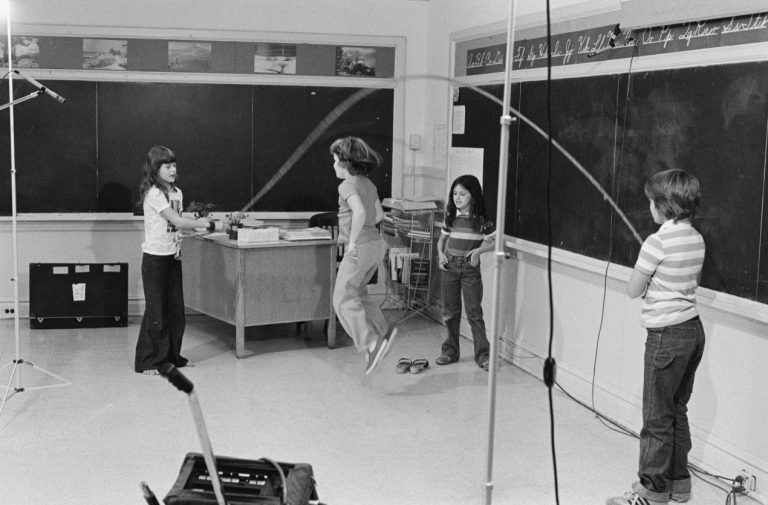

Children jumping rope, Blue Ridge Elementary School, Ararat, North Carolina. Photo by George Price Jr., 1978. Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project.

This post is part of a series of posts called Staff Finds During Difficult Times, in which staff members discuss collections and items that have been inspiring them while they are working at home during the COVID-19 pandemic or in other difficult circumstances. Find the whole series here!

As I work from home and keep to the rules of social distancing, neighbors’ children are busy doing the same. The usual life of play and playgrounds has been put on hold. Yet there are ways that kids are keeping their folk traditions alive. Chalk drawings are appearing on the streets and sidewalks. Hopscotch grids appear on sidewalks, even though children can’t gather in groups to use them. Perhaps they make them to use with their siblings, or for their neighbor friends to use even when they can’t be there to play too. Somehow childhood traditions continue in spite of the unusual situation we are living through. On my street, where there is little traffic, a series of chalk footsteps appeared with instructions for taking giant or baby steps. A track was drawn for bicycles to follow. Kids are communicating with each other from a distance, whether by code, by electronic devices, or by shouting across the street, and play is not on hold.

In this context, I find some inspiration about the vitality of children’s play traditions from the American Folklife Center collections. I wonder if others might find some inspiration there as well. I thought that this might be a good time for students, parents, and teachers to have some examples of children’s play at hand. It might be a way to get conversations going about how important play traditions are, what everyone misses, and what they are doing instead. Through the American Folklife Center’s collections, it is possible to look at children’s play in different times. The Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project, which took place from 1978 to 1979, includes recordings of children’s playground folklore recorded in two fourth grade classrooms in North Carolina. Students might be interested to listen to the recording of games and rhymes of these fourth graders documented in 1978 presented below to compare with their own. What has changed since the recording was made? What hasn’t? Do some of these rhymes and songs sound old fashioned? Or is it surprising that they were collected so long ago?

The recording in the player below documents a wealth of rhymes, songs, games, riddles, sayings, jokes, and other folklore that belongs to children. Though they might gather some of their lore by talking with parents, grandparents, and other family, much of children’s own folklore is generally passed on from one child to another. This is often different from the other “children’s folklore,” the songs and rhymes that parents teach their kids on purpose, though there is some overlap as a mother might teach a child one of her own favorite jump rope rhymes that she learned from other girls as a child, or a dad might tell a child some of the jokes he liked to tell when he was a kid. There are many rhymes, games, and songs of playgrounds and after school play that have passed from child to child for generations, with very little help from adults. To folklorists this knowledge children pass on is valuable. Each generation of children may give their own twist to the folk games, rhymes, songs, and jokes that are passed down to them, but it is surprising how much is retained over many years. New items are added and old ones are sometimes updated with references to current events or new technology. But much remains the same.

In the recording, folklorist Patrick Mullen talks with children in Mrs. Currier’s fourth grade class at the Blue Ridge Elementary School, Ararat, Virginia, in 1978, and asks them to perform some rhymes, songs and jokes. The first is “Cinderella Dressed in Yella,” a jump rope rhyme still familiar to many students today. Next, some clapping songs are demonstrated by girls who volunteer. These are followed by some folksongs sung by both boys and girls. Hear it all in the player below:

Some of the rhymes were used for clapping games and jump rope, and some are still familiar today. These rhymes were almost entirely girl’s folklore at the time of this recording. As jumping rope for health has become more common not only for both boys and girls but for grown men and women, some of the traditional rhymes have become less exclusively the girl’s domain. But, in the recording above, it is noticeable that the boys drop out when jump rope rhymes or clapping games are asked for, but speak up when it comes to riddles, jokes, and songs.

Two girls in Mrs. Currier’s fourth grade class play a clapping game with a rhyme for folklorist Patrick Mullen. Blue Ridge Elementary School, Ararat, North Carolina. Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project, Library of Congress. Photo by Patrick B. Mullen, 1978.

When Mullen asks for more rhymes the children hesitate, so he asks for, and gets, “Down By The River,” and “Cranky old Jalopy.” Some of his fieldwork techniques show in the way he gets the children to participate in making these recordings. He already has talked to the children and has some idea what they know, so that when they don’t think of another rhyme for the recording, he can prompt them. But he wants the kids to explain their own traditions. So he asks questions, like, “what happens next?” and “what happens when somebody misses?” At about 3:30 minutes into the recording, the children demonstrate some clapping games. These rhymes are sometimes also used as jump rope rhymes, although some children will know them as either clapping games or jump rope rhymes. You will hear Patrick Mullen asking more questions and encouraging the children to keep the game going.At the beginning of the recording Mullen asks the children to demonstrate a jump rope rhyme. They chant “Cinderella Dressed in Yella.” In this rhyme Cinderella does something, in this case makes a mistake and kisses a snake, and then they must count the number of doctors that had to be called. This leads to counting as the rope spinners speed up and see how long it takes for the jumper to miss. This rhyme was collected in the United Kingdom by Iona and Peter Opie in 1972 (listen to their recording on the British Library site). They thought it must be a new rhyme at the time, inspired by the pop song “Cinderella Rockefeller,” which was first performed in 1967. The jump rope version is not very similar to the pop song, except for the idea of rhyming Cinderella with something. But there are no known versions of the rhyme dating to before the song. There are now many versions found in the English speaking world, continuing to be sung for jump rope long after the pop song has faded into history.

Even if a folklorist knows a tradition pretty well, sometimes they can learn something new by asking questions like this, because there are many variations in the rhymes and in the games. All the children may not play it the same way. So he asks “Where did you learn that?” Which gives him some information about how the rhymes are passed along. For playground rhymes and songs, it is often children who teach other children, though sometimes children learn from adult relatives. The children sing some songs, and at about 12 minutes into the recording, two girls sing an African American game song, “My Left, Right, Left.” When Mullen asks “Where’d you Learn that?” the girls say, “Lavera,” who turns out to be a girl’s cousin from New York, New York. So we see that one way these songs can travel long distances is through family members who live far away.

We know that children’s folklore travels a long way, even crossing oceans. Travel is one way that children meet each other and trade folklore. Migration and immigration also play a role. Some African American songs and rhymes, both of adults and children, have roots in Caribbean traditions, as people moved from the islands to the North American mainland, beginning in the 18th century. Similarly, Spanish language folklore has traveled from Puerto Rico and from Spanish-speaking countries as people move.

Fourth grade students in Mrs. Currier’s class sing songs for folklorist Patrick Mullen. Blue Ridge Elementary School, Ararat, North Carolina. Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project, Library of Congress. Photo by Patrick B. Mullen, 1978.

At about 14 minutes into the recording, Mrs. Currier organizes her students to sing a funny song “Scratch My Back.” This is a song both the boys and girls know. The students sing some more songs including “One Two, Buckle My Shoe” (a hopscotch song), “The Itsy Bitsy Spider,” and “Bingo” a song Patrick Mullen asks for. These are songs that most children know, and so the adults encouraging some familiar songs ensures that all the students have a chance to participate in the recording session.

At about 20 minutes some children ask if they can sing “Miss Lucy,” one of my personal favorites. This playground song has a long history and has been collected in many versions in the English speaking world. The version you know may be very different than the one you hear on this recording, but usually there is Lucy, a bathtub, a doctor, and a lady with an alligator purse. Some have many verses with surprising adventures. It is used in various ways: as a song, a jump rope rhyme, a clapping game, a stick game, and perhaps more. The versatility of the song probably has contributed to its spread and its many variations.

I find this recording of fourth grade students interesting not only for the folklore that the children carry and pass on to each other and what they may learn from it, but also because it shows how a folklorist works to collect folklore from children.

Kids who are restricted in how they can play with each other during the current COVID-19 crisis might find a time to reflect on their own folklore because it is something that is missing. Perhaps they might like to write some down songs and rhymes to make their own collection. They might also want to write something about how they play during a time of social distancing. If readers want to share, examples can be added to the comments on this post. The American Folklife Center’s Explore Your Community Poster, listed in the resources at the bottom of this blog, has suggestions for projects for high school age students as well.

I look forward to the day that children’s play gets back to normal. But in the meantime, I am sure kids will find many ways to keep that playground spirit alive.

Resources

Blue Ridge Parkway Folklife Project Collection, Library of Congress.

Hall, Stephanie, “Collection Spotlight: Children’s Songs from the Virgin Islands,” Folklife Today, December 7, 2017.

Hall, Stephanie, “Explore Your Community: A Poster for Teacher’s and Students, Part 1,” Folklife Today, June 4, 2018. Included is a link to a PDF of the poster. Links to parts 2 and 3 of this blog are available in the post.